The city of Lowell, Massachusetts, is widely known for its role at the forefront of North America's Industrial Revolution, and for the young farmwomen who came to find employment in its textile factories, the storied Mill Girls. The city boasts a number of somewhat lesser-known firsts: the first Civil War casualties, the first city in the country to use telephone numbers, the first mass-produced soft drink (Moxie), and the first U.S. city with a desegregated and co-educational high school, to name a few. But there's one first that has been totally forgotten over the years. In the winter of 1914, Lowell was the first, and perhaps only, city in the country to put anyone on trial for dancing the tango. As it turns out, it wasn't even a tango the defendants were dancing, but that only adds to the absurdity of the tale, a tale that has a lot to say about the social mores of the era and human behavior in general.

What follows here is based on years of research and, while some of the included dialogue is clearly informed fiction rather than strict quotations, a great deal of the story has been pulled verbatim from newspaper reports of the trial.

Central Street at night c.1919 (adapted from Coburn's History of Lowell and its People, vol 2)

The evening of February 19th, 1914 was chilly and the forecast included snow. Even so, it was a far cry from the sub-zero temperatures of the preceding week or the brutal Valentine's Day storm that had nearly paralyzed the city. Horse-drawn plows hired by the streetcar company and teams of city-paid men with shovels had since rendered the downtown streets reasonably clear, but vast piles of snow still waited their turn to be carted away and dumped in the river. Fortunately for Miss Angelina Marcotte, this wintry obstacle course was well-lit by electric streetlamps, their glow glinting off the paving stones and making the icy snowbanks sparkle.

Angelina hurried along Merrimack Street and around the corner onto Central; from there she could see ahead to where Gorham Street forked off to the right. Once she was on Gorham, Lincoln Hall would be just a few doors down on the left.

"Je déteste le froid," the petite brunette muttered to herself, her breath visible in the frosty air. Angelina trod carefully over a patch of sidewalk where a storeowner had delayed shoveling too long and a thousand passing feet had packed the snow into solid ice. "Tant pis," she sighed. "At least it's warmer than last week. And at least ce n'est pas Québec!" she added with a shiver. "Brrrrrrrrr!"

Despite the annoyances of getting to and fro in the winter, it was prime dance season. Better a bit of a chill on the way than everyone dripping sweat on each other. And Angelina knew that the cold wouldn't bother her as much on her walk home; by then she would be warm from the dancing and the fresh air would be a pleasure.

What Angelina didn't know—what she couldn't have known—was the impact this particular evening of dancing was going to have on her life.

Dancing has always been viewed with suspicion by a certain subset of the population and, in 1914, with Ragtime flourishing and Victorian mores passé, the naysayers were fighting hard to hold back the tide of immorality they saw flooding the dance floors. A particular target of their ire were the so-called "animal dances." The previous century's carefully laid-out dances with their preset steps and sequences were now being replaced by a menagerie of trotting, shuffling, swaying, hopping, limping, kicking, stalking, and bobbing couple dances. These new dances bore names like the Turkey Trot, the Bunny Hug, the Chicken Flip, the Kangaroo Hop, the Grizzly Bear, the Camel Walk, and the Lame Duck. "The Kitchen Sink," though lacking an animal moniker and more a type of dip than a whole dance, was also frowned on because the couples who indulged in it tended to throw in every possible jaw-dropping flourish except said sink.

Yet worst of all in the conservative crowd's eyes was the tango. It came from Argentina which made it seem exotic. It involved twisting motions and hip movements seen by some as sexual. It was often danced in a very close hold. And it included dipping moves that literally violated the positional norms of "upright" citizens. On top of that, despite the best efforts of Western dance-masters to tone the dance down for polite society, Vaudeville would often mount sensationalized stage interpretations of the tango and warp it into something even more scandalous than the untamed original. For a great many people, particularly non-dancers, the Vaudeville version was all they knew of the dance.

Still, the tango's biggest sin may have been in its history. Coming from a time and place where men far outnumbered women, tango was frequently done by two men. If a man wanted a female dance partner, oft times his best bet was to seek one out at the nearest brothel. When done by two men tango was a preening competition; between a man and a woman it suggested a negotiation for sex. And in this negotiation, the woman had the upper hand because she was a creature of rare value while men were plentiful.

Across the Western World of the nineteen-teens women were throwing away their corsets and fighting for the vote. They were showing their ankles and refusing arranged marriages. And along comes a dance where the woman is not some demure follower: she has agency, she has power, and she makes each move her own. The tango embodied the very message the traditionalists were trying to quash. And "tango" became a catchword for every dance that these folks felt threatened the social order.

But none of this was on Angelina Marcotte's mind that Thursday evening. The slight twenty-year-old simply wanted a break from the drudgery of the Worthen Street boarding house where she was employed. This evening's dance at Lincoln Hall wasn't exactly next door but it was less than a mile's walk. Angelina had spotted the advertisement in the Lowell Sun and decided to go, knowing the day's exhaustion would drop away once she heard the dance music.

As she approached the Donohoe building, whose upper floors held the hall, it was clear she wasn't the only one eager for some fun. Catching the eye of another young woman who was also threading her way toward the door, Angelina smiled and commented: "You have to give credit to the Buffalo Club, no? They don't waste money on fancy newspaper announcements but they always draw a crowd."

The other woman laughed and responded: "So true. Just four words tucked here and there in the paper—'Buffaloes, Lincoln, tonight, Miner's'—and everyone flocks in. They don't put much money into fancy decorations for the hall, either, although I do remember at least one of their dances having a large picture of a Buffalo hanging from the balcony.

Angelina nodded back. "Men," she replied and rolled her eyes. "That's what happens when a bunch of boys are the organizers. But we're here for the dancing and the company, not the crepe paper, aren't we? Miner's Orchestra is always a blast. It's said that Mr. Miner started the group with mostly high school students, so regardless of who's on stage with him tonight they're sure to be young and full of energy!"

Front of Donohoe building (taken 2022 by R. Evans) with the stairs that once led to Lincoln Hall visible through the center door

And then Angelina was through the door and up the stairs and her new acquaintance was gone in the crowd. The Donohoe building might be all commercial storefronts at ground level—in February of 1914 both street level and basement held the businesses of Henry Carr: furniture, tobacco, and a billiard parlor—but the second floor included a function room, the third floor was home to Lincoln Hall itself, and the fourth level allowed access to the galleries overlooking the main hall. Angelina paid for her ticket, received her dance card with its tiny pencil hanging by a silken cord, checked her coat, and replaced her buttoned boots with a pair of dry shoes more appropriate to the dance floor. After that it was time to chat and flirt and find a partner for this dance or that.

Also among the young people in the hall was Frank Hennessey. He was a few years older than Miss Marcotte and the two were only vaguely acquainted. Frank arrived at the dance about quarter to nine, purchased his ticket at the door under the watchful eye of Patrolman John Swanwick, and settled himself in the gallery to enjoy the scene below. It was good to get out of the cramped confines of the boarding house where he lived with his widowed mother and three of his sisters, and Frank found himself musing once again that it was just as well his other three siblings had found places of their own over the past few years given how much more cramped home could have been.

"Come on, Frank," prodded one of his friends, "You're tall and good looking, and gainfully employed over at Curley's Market; I'm sure these ladies would consider you quite the catch. Get down there and ask one of them to dance!"

Frank shook his head and replied wryly: "They might consider me a catch off the dance floor, but I'm not quite so sure about on it!" He shrugged and sat back in his chair. "Maybe later."

"Later" turned out to be after the intermission had ended, around about 10:30. Frank went downstairs to check his overcoat before snagging a partner and heading out on the dance floor. They'd just started a simple waltz when his partner suddenly looked unhappy.

"Is my dancing that bad?" Frank inquired.

"Oh, no, it's not that. I just saw his Royal Highness the Dance Inspector come in with his trusty sidekick."

"You mean Clark and Swanwick? The Mutt and Jeff of the Lowell Police Department?"

"Shhhh! They're headed this way!" she replied, moving back a bit in an attempt to put another inch or two of air between Hennessey's midsection and her own.

But the two policemen passed the pair by. A nearby couple was not so lucky. After a few words from Special Officer Clark, the couple made their way off the floor, red-faced with embarrassment and clearly annoyed.

By this time it wasn't just Frank and his partner watching the action. A loud hiss began to roll through the crowd as the dancers expressed their displeasure with the officers. Clark scowled back at the group, and Frank could have sworn he heard the officer mutter: "Keep that up and someone's gonna be sorry."

But the rest of the waltz passed uneventfully, as did the two-step that followed, and Frank lost track of where Clark and Swanwick were or who they had in their crosshairs. After escorting his two-step partner off the floor, Frank glanced around for a partner for the final dance on the evening's program, a schottische. His eye caught Angelina's and he hurried towards her.

"May I have the next dance?"

Angelina smiled and took his hand in answer. As Frank led her out onto the dance floor he asked: "Have you been having a good time? How's life in Lowell working out for you? I seem to recall that you only recently moved here from Manchester."

"It's only recent by your standards, you having been born here!" she replied a tad indignantly. "I've been in town a whole year."

Just then the music started and it was either dance or be run over by the crowd. The schottische being a lively dance, and one that moves around the room, standing and chatting in the middle of the floor was bound to cause a traffic jam. The couple danced a few phrases of a basic schottische before Angelina paused and spoke.

"Do you know how to do a five-step? It was the schottische to do when I was growing up in New Hampshire."

"I'm afraid not."

She pulled him off to the side and began to explain: "Look, it's easy. You forget about the whole second part of the dance, the step-hops, and just do the first part, only replace the hop in it with a chassé.

Hennessey looked bewildered.

"Here, like this." Angelina reached up and put her hands on Frank's shoulders while he took hold of her waist. She was several inches shorter than her partner so it was a bit awkward trying to push him through it.

"One, two, step-together-step…" Their feet got tangled and the pair almost fell, clutching each other tightly in their effort to stay upright.

"Gee whiz, I'm sorry..." began Frank, but Angelina was looking past him. She'd spotted Officer Clark watching them and shaking his head.

"Uh, maybe I'll show you some other time," she replied straightening up. "Let's just do whatever version you like."

The music went on for a good bit longer and by the time it finished the pair were making a reasonable go at a decent schottische. With barely a pause, the band on stage went into a waltz.

"It's the waltz home," noted Hennessey. "Shall we?"

The last waltz of the evening was inevitably quieter than the earlier ones. The whole crowd was tired. Angelina rested her hands against Frank's chest while his arms encircled her and his hands rested on her upper back. It was uncomfortable looking up at him from that close and it wasn't long before she let her head rest on his chest. Frank's hands slid down to land low on his partner's waist. Their waltz steps were short and swaying, and every so often they would dip into one knee, a popular waltz move of the day.

When the dance ended the pair said their goodnights before separating to get their things and bundle up for the walk home. In the cloakroom, Frank encountered Officer Clark.

"What's your name?" demanded Clark.

"Frank Hennessey, sir."

"And your address?"

"34 Arlington Street."

"You're sure that's right?" Clark asked suspiciously. He'd had a hard time getting any information on this fellow; the three blokes he'd asked in the hall had feigned ignorance when asked if they knew Hennessey's name.

"It is."

Without another word, Officer Clark turned on his heel and went in search of other prey. Frank looked after him uneasily, shrugged, and headed out alone for home.

Clark caught his other quarry on their way out the door. Angelina felt a tap on her shoulder and turned to see the dance inspector behind her. He pulled her to one side, out of the path of the partygoers pouring from the building.

"I need your name and address, young lady," Clark announced, his pencil and notebook at the ready.

Angelina didn't like the sound of the request, but she did as she was told and offered: "Angelina Marcotte, 66 Worthen Street, at Rose Duprey's boarding house."

Clark jotted in his notebook for a moment before standing silently to frown at Miss Marcotte.

Angelina began to fidget. "May I go now, sir?"

The patrolman gave a nod. Angelina could feel him staring at her back as she pulled her coat tightly about her and hurried toward home. The officer's attention worried her but she could think of nothing she'd done wrong. Surely that would be the end of it.

Patrolman John H. Clark had been assigned special duty only weeks earlier, at the beginning of January. In his new role as Lowell's dance hall inspector, he was to attend public dances about town and caution dancers if he believed they were behaving immorally. But Clark had been instructed not to make any arrests without first consulting his superiors, and so his report from this night's doings went up the chain to Police Superintendent Redmond Welch. Unfortunately for Frank and Angelina, Welch agreed with Clark that it was time to take action against the sinful dancing infecting Lowell. And, like Clark, Welch felt that making an example of these two was a good place to start.

By Saturday, February 21st, Supt. Welch had sworn out arrest warrants against the pair. Late that day, Officer Clark and an Inspector Walsh arrested Frank Hennessey at Curly's Market on John Street where he worked as a clerk and delivery boy. The charges were lewd, wanton, and lascivious actions. Hennessey insisted that he hadn't danced that badly, certainly no worse than everyone else on the floor.

The officers didn't serve the warrant on Miss Marcotte until 1:30 the next morning. They found Marcotte at home, in bed, and insisted on remaining in the room while she dressed (which says quite a bit about the officers' rather selective sense of propriety). Angelina told the police that there was nothing going on between her and Hennessey, that she was just learning some of the steps, and that she hadn't known that he was such a bum dancer when she agreed to dance with him.

Word spread quickly about the arrests, not only across town but across the country. The crusade against the tango and its kin was not unique to Lowell, or to the United States for that matter—one enterprising police chief in Germany had arranged a professional tango demonstration for his officers so they knew what to look for—but Lowell was the first city in the States to actually arrest someone for improper dancing and press charges. While some folks were righteously relieved that action was at last being taken, others thought the whole thing an entertaining farce, and still others simply wanted to get a glimpse of these scandalous dances that had everyone in a tizzy!

German Police learning how to recognize a tango (adapted from Le Petit Journal, December 1913)

By Monday morning the Boston Globe was trumpeting on their front page "COUPLE IN LOWELL ACCUSED OF TANGO. To Face Charges in Court Tomorrow Morning. Frank Hennessey and Miss Angelina Marcotte Arrested on Warrants."

"LOWELL, Feb 22—Frank Hennessey and Miss Angeline Marcotte were arrested on warrants early this morning in connection, it is alleged, with dancing the tango at a dance in Lincoln Hall last Friday night.

"Patrolman Clark has been detailed by the superintendent of police to attend public dances in this city and to caution dancers where he believed they were violating the law.

"On his evidence a warrant was issued against the accused. The charge against them Tuesday morning will be unbecoming behavior."

On Tuesday morning, there was a large crowd awaiting the proceedings at the Lowell Police Court on Market Street, including a number of reporters. The Boston Post printed a statement from Miss Marcotte saying: "I was not dancing the tango. I do not even know how to dance it or any of those new dances. My partner did not know how to dance the five-step schottische and I was showing him."

Superintendent of Police, Redmond Welch was also quoted: "We don't know what they call it, but we call it rowdyism. They can dance and dance, so long as they dance it properly. We are not trying to stop the tango any more than the waltz. What we do insist on prohibiting is immoral dancing of all sorts."

Hennessey's attorney, J. Joseph O'Connor, said that bringing such a charge against two young people was "simply awful" and heaped condemnation on Supt. Welch's head for swearing out the warrant.

And, while the officers who'd been at Lincoln Hall that night weren't sure just what dance the couple had been doing when they so offended the law, they were quite certain that they had seen "wiggles."

Lowell Police Station & Court c.1925 (adapted from Lowell Sun, March 1926)

When that morning's docket finally got to the so-called tango case, the defense attorneys requested a continuance, which the judge granted, and the actual trial was postponed to the following Wednesday, March 4th. A few other items were taken care of before the court moved on: the defendants entered pleas of not guilty and furnished bail, and Judge Thomas J. Enright granted a motion by Atty. O'Connor demanding the prosecution specify the alleged acts of "lewd behavior" being charged. Superintendent Welch was given until the coming Saturday, February 28th, to supply the defense with a "bill of particulars" detailing the offending behavior.

According to the Lowell Sun: "There was an air of unfeigned disappointment in the courtroom when it was seen that the case was not to be tried, for the anxious spectators expected demonstrations of the tango as it is and as it ought never have been."

Despite their frustration, the public's hope for an entertaining tango exhibition remained high, especially when it was rumored that Marcotte's lawyer, George H. Allard, had suggested to Judge Enright that Special Officer Clark himself should be required at trial to demonstrate the moves that had led to Frank and Angelina's arrest.

Following the hearing, on the advice of counsel, both defendants declined to speak further about the case except through their attorneys.

The wire services picked up the story, although at least one of them apparently had it wrong since several newspapers reported that the defendants were tango instructors despite neither of them actually knowing the dance. A newspaper in Nebraska printed a tongue-in-cheek note about the upcoming trial complete with a short poem, its final rhyme self-censored.

"Miss Angelina Marcotte and her escort, one Frank Hennessey, were taken before the cadi in Lowell, Massachusetts, the other day on the serious charge of having tangoed at a public ball. A stay of proceedings was granted both offenders that they might assemble witnesses and secure the help of attorneys in battling with a most unpleasant situation. Lowell is a city that will stand for a good deal that is shocking and inexcusable, but it draws the line at the loud and high-colored in dancing."

"So Hennessey is given one

For cutting up fool-capers,

And Angelina is undone,

According to the papers.

The old square dances there were thought

Quite sane and on the level,

But when they tried the turkey-trot,

They raised the very mischief."

By Friday, the 27th, the Bill of Particulars had been filed. The Lowell Sun printed excerpts:

"That the acts relied upon to prove the allegations set forth in [the] complaint took place in Lincoln hall on Gorham street in said Lowell on and during the evening of Feb. 19, current."

"That, at said time and place a certain public diversion or dance was held."

"That a large number of persons, both male and female, were present as participants in and spectators of said dancing."

"That certain police officers of the city of Lowell were also present to maintain proper decorum while dancing was in progress."

The bill cited "indecent postures and attitudes" on the part of the couple and said that the pair had "continued to dance with somewhat reckless abandon despite the protests of the police officers." The bill also stated that Hennessey and Marcotte's actions constituted "a violation of section 46 of chapter 212 of the revised laws of the commonwealth, having to do with lewd and lascivious conduct."

Chapter 212 of the Revised Laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is titled "Crimes Against Chastity, Morality, Decency, and Good Order," which, to this writer's ear, sounds a lot like a hammer in search of a nail.

Section 46 casts a wide net regarding who may be imprisoned under the law: "Rogues and vagabonds, persons who use any juggling or unlawful games or plays, common pipers and fiddlers, stubborn children, runaways, common drunkards, common nightwalkers both male and female,"—apparently there are a good many things that are okay just so long as one isn't "common" about it—"pilferers, lewd, wanton and lascivious persons in speech or behavior,"—this is the charge levied at Marcotte and Hennessey—"common railers and brawlers, persons who neglect their calling or employment, misspend what they earn and do not provide for themselves or for the support of their families, and all other idle and disorderly persons, including therein those persons who neglect all lawful business and habitually misspend their time by frequenting houses of ill fame, gaming houses or tippling shops."

The fascination with Lowell's dance case continued to grow. Wednesday morning saw reporters roaming the downtown area; one of them snapped a photograph of Miss Marcotte and Attorney Allard leaving the Hildreth building where Allard had his office, a good two blocks away from the courthouse.

The Lowell Courier-Citizen reported that "long before court was opened to the public a crowd of several hundred surged about the [police] station in Market Street, and when the doors were finally thrown open there was a rush that put to shame a bargain counter scramble. Three officers were on duty and they held back everyone who could not prove that he or she was in attendance on court business. All kinds of excuses were offered and a few of them went, but many of them failed to get by the cordon."

Left: Angelina Marcotte with her lawyer, George Allard. Right: Crowd outside the Police Station (pics adapted from Lowell Courier-Citizen)

Other reports note that a large number of the excluded remained in the street, in the cold, for hours waiting for news of the trial—or even better, a chance to somehow grab a seat inside.

From the Lowell Sun: "The excitement in and about the Market street building this morning was the most intense of any witnessed there for many moons. Not since the Blondin murder, or perhaps the days when the great textile strike was at its height, and rioters were being carted to the police station as fast as the black Maria could take them in, have so many sought admittance to the police court, where officers were on guard above, and below stairs…It was terrible confusion for such a little thing but there's no accounting for the acts and tastes of the human family.

"The only thing missing was the over-crowded gallery and that is a thing of the past…The occupancy of it was discontinued by order of Judge Enright who feared that some day it might give way."

The players in this Edwardian reality show became local celebrities. Angelina Marcotte was subjected to the most scrutiny. Reporters described her as wearing a long, green topcoat, a dark brown skirt with a dainty slit on one side, a jaunty hat of either brown or blue, black velvet-topped button shoes, and a large set of white furs. From the photographs one gathers that somewhere along the line she picked up a small bouquet, presumably from an admirer. When she first made her appearance at the courtroom that morning she appeared uneasy, but before long she relaxed and smiled to her many admirers.

Frank Hennessey, it was reported, was a fresh-faced, good-looking young fellow who did his best to stay in the background.

The arresting officer was also of interest. From the Lowell Sun: "Officer Clark, the animal dance inspector, came in for more than his share of attention. He was pointed out as the man responsible for the arrest of the two tangoers, and the one officer who is capable of deciding as to the propriety or impropriety of the dance. Not only does he pass upon the tango, but he also penetrates the mysteries of the lame duck, Argentine, the chicken flip, bunny hug, grizzly glide and other kindred dances."

Of course, the defendants had not been doing any of those dances, yet they were repeatedly called tangoers or tangoists by the papers. And the whole affair was widely referred to as the Tango Trial, making for pleasantly alliterative headlines that played on the dance's infamy. One reporter even assigned inventive labels to the concerned citizens whose eagerness to stamp out modern dancing had prompted the arrests in the first place: Antitangoists or Tangophobists.

The tiniest colorful details about the trial made it into the papers. The courtroom was described in the Boston Globe as "the quaint old courtroom in the ancient market building with its balcony shut off from use because unsafe, with its little bronze statuettes supporting the lamps on judge's bench and bailiff's desk, with its wonderful hat-rack in the bar enclosure—a twisted rugged vine of cast iron, branching into tendrils on which the attorneys hang their hats."

On the morning of the trial, the police court waded through a number of minor docket items prior to Hennessey and Marcotte's case being called right around noon. By that time, many of the spectators in the courtroom were getting restless and Judge Enright threatened to clear the courtroom if they didn't quiet down. But it wasn't long before their wait paid off.

Almost immediately after the trial opened, Atty. O'Connor announced that the bill of particulars provided by Supt. Welch was entirely inadequate and failed to give in detail the alleged actions of the defendants. "It is words and little else," he declared.

The trial moved forward anyway.

Police Superintendent Welch acted as prosecutor and his first witness was John J, Flaherty, clerk of the license commission. Flaherty testified that Lincoln Hall had had a license to hold a public dance on the night of the alleged crime. O'Connor declined to cross-examine the witness, but he did protest the submission of what he considered irrelevant evidence since the offense in question could equally well have been committed in a private hall as at a public event.

Up next was Officer Clark. He testified that he got to the hall on the night of February 19th at 10:45 p.m., just as the first dance following the intermission started.

"I saw the defendants there that night," Clark stated, "and I spoke to them. I told them they'd have to stop such actions…"

"What actions?" Supt. Welch asked the witness.

"Indecent actions."

"Oh no," broke in Judge Enright, "you must describe these actions."

Clark moved his shoulders about and swayed back and forth in answer. The spectators in the packed courtroom grinned appreciatively.

"Did they dip?" asked Welch.

"Yes." Clark ludicrously bobbed up and down a few times to demonstrate. "I warned the couple three times, and it was their dancing after the warnings that prompted the complaint."

The court still was not satisfied, nor was Hennessey's attorney. "I object," complained Atty. O'Connor. "You must describe exactly what they did."

"It was the way they moved their bodies…" Clark began.

"What were these movements?" interrupted Welch.

Clark stood up and attempted to portray the defendants' leg positions and movements as he observed them.

"One movement was this way," said Clark, bowing back and forth, "and the other was this way," and he rocked from side to side. The patrolman got a good bit of hip and shoulder action into the demonstration before pausing once more to explain: "They had their arms around each other so that their hands rested on each other's behind. Their bodies were pressed close together and in this position they walked around the room."

Judge Enright—apparently familiar only with old fashioned, patterned dancing rather than the more recent lead-follow styles—interrupted: "When they're dancing that way, and the woman's body goes back, does the man's body go toward her?"

"They move at the same time with their bodies tight together," replied Clark.

"I just don't get it yet," said Judge Enright.

"Suppose," suggested Supt. Welch to the witness, "that you and Officer Swanwick show what they were doing."

"I object to this!" exclaimed Atty. O'Connor.

Judge Enright replied soothingly: "But this man has explained as well as he can, and I don't get it yet. It is important to know just what was done."

Accustomed as Judge Enright was to the predetermined steps of nineteenth-century contras and quadrilles, the idea that two bodies could move around the room in unison, the woman guided solely by subtle signals from the man delivered on the fly, was clearly baffling.

"Well," O'Connor conceded, "I don't wish to withhold any information from the Court. On with it then."

Officer Swanwick came forward and a space was cleared in front of the judge's bench. One reporter would later comment that the name Swanwick was "a misnomer in both syllables," for Patrolman Swanwick was slightly shorter, decidedly plumper, and with a ruddier complexion than the classically handsome Officer Clark. Reluctantly, Swanwick assumed the lady's role. The two patrolmen reached round each other to put their hands on each other's revolver and handcuff pockets—this was noticeably more difficult for Clark given his partner's larger girth. Then the tall, pale patrolman pushed forward and the "lady" backed up six inches. They did this a second time, and a third, until they'd made ten steps or so across the space, though neither man seemed to be displaying the sways and wiggling of which they'd accused the defendants.

The officers appeared somewhat flushed and embarrassed during the demonstration, their faces frozen in grim determination, yet duty called and on they went, doing their level best to show the naughty dance.

Just as Clark looked ready to quit the dance floor and return to the witness box, Officer Swanwick spoke up: "His Honor hasn't seen the dip yet. You know…they dipped like this." Swanwick promptly tried to illustrate his words but he wasn't constructed for the move. As a result, Clark was unexpectedly pulled off balance and nearly dropped his partner. Swanwick made a rather strangled grunt. Still, the two persevered and executed a series of squats that gave the impression of trying to sit in each other's laps.

The exhibition finally ended. But if the prosecution was depending on it to strengthen their case, it was a tactical error. Every seat in the courtroom had been occupied when the officers began their "dance," but the spectators were on their feet at the first step, and roaring with laughter before the third was made. Clerk Trull pounded with his gavel but it was some time before the laughter died down.

As for Hennessey and Marcotte themselves, they had, until this point, sat together unspeaking on a bench off to the side, both chewing gum in a sort of quiet duet. During Clark's early testimony Angelina merely gazed at the witness with a distracted air, but now she giggled and smiled scornfully in response to this absurd representation of her crime.

Swanwick turned a brighter shade of pink than usual. Clark, too, was flushed as he returned to the witness stand.

The newspapers had a field day with the story.

The Lowell Sun declared the demonstration a "sight for the gods" and announced that those in the know decreed Swanwick the better dancer "with a certain gracefulness about him that seemed to take the curse of the terrible dip that makes the tango an outlaw."

The Boston Post referred to Swanwick as "cherubic" and headlined one article "Ludicrous Display of Bluecoats' Idea of Improper Steps at Hearing of Lowell Dancers."

Meriden, Connecticut's Journal stated that witnesses of the demonstration "said afterward that anyone who danced as they danced deserved at least a hundred years and maybe hanging."

The Scranton, Pennsylvania Tribune joked that after the performance, patrolmen in Lowell were pledging that "so help them, even though all the tangoers this side of Argentina writhe before them, they will never again make a terpsichorean arrest." The paper also said that the officers called upon at court "had ruined two uniforms, spoiled two shines, and nearly broke four legs" trying to show why they had arrested the young couple.

Eventually the courtroom settled down again, and Clark's testimony resumed. Under questioning by Supt. Welch, Officer Clark explained to the court that the defendants were not arrested at the hall on the night of the dance, a Thursday, but on the following Saturday night. He told of conversations he had with the defendants during their arrest when he read the warrants to them.

Then it was Atty. O'Connor's turn to question the witness. O'Connor took Clark through a biographical sketch and then set about determining his qualifications as a judge of dancing, his level of knowledge regarding the law in question, and his understanding of the rights of police officers in arresting anyone.

"What class of crime would the conduct of the dancers come under?" Atty. O'Connor inquired.

"Felony," replied the witness.

"Do you feel that's warranted? To send these young people to state prison?"

"No, I would have preferred a misdemeanor charge. But the statute under which Mr. Welch chose to charge them is a felony. My job was to arrest them, not to proffer charges."

"If you're familiar with the section of the statute under which the complaint was made, why then did you consider a warrant necessary? That section states that a warrant is not necessary when arresting a person, or persons, for 'lewd, lascivious and wanton' conduct."

At this point Judge Enright cut in: "It's clear that this cross examination is going to take some time. Let's break for lunch. Court is adjourned until 2 o'clock."

"All rise," demanded Clerk Trull.

The air rustled and shifted as the crowd rose and Judge Enright departed. Officer Clark stepped down from the witness stand with relief. Reporters rushed from the room to submit their stories for the evening papers, the local reporters heading right to their downtown offices and the ones from Boston and beyond in search of telephones.

The spectators stood and looked at each other. A break from the stuffy courtroom, a breath of fresh air, and a bite to eat would be welcome, but they'd fought so hard to get these seats, and rumor had it there were a few hundred people still out on the street hoping to get in. Would the police let them stay in their seats during the break or would they clear the courtroom? Would the spectators have to wait in line outside all over again? And did they even want to stay for the second session or should they just go home? It would be hard to imagine a more entertaining spectacle than the one they'd already had the pleasure of witnessing; perhaps they should call it a day and let someone else have their spot. Whatever their individual decisions, by 2:00 the courtroom was again packed and the trial moved forward.

As the trial was getting back into swing inside, one other minor bit of drama occurred in the corridor outside. Members of the police department's liquor squad had been posted at the head of the stairway leading to the courtroom with instructions that no one was to be allowed in after 1:45 unless they were witnesses or had some business connected with the court. Along about 2:30 an elderly Black man began slowly making his way up the stairs.

"Save your energy," called down one of the officers. "You'll not be allowed to enter."

The man stopped and looked up. "I sure must go in," he pleaded, "for it is very important that I see just what is going on in there."

A reporter standing at the head of the stairs with the officers interceded. "Come up here and explain."

Coming up the stairs further, the gentleman repeated: "I just have got to see that there trial. It's a matter of importance."

The officers began to cross-examine him. "What makes you think that you should be able to get in when we've already left all those other folks standing out in the cold?"

"Why, you see, sir, I'm the janitor of the Tewksbury town hall and I've got to find out just what this here tango is, so that I can stop it if any tough guys try to start something at one of our events."

The officers exchanged hurried glances and made their decision; the fellow's reasons sounded good to them. The janitor from Tewksbury was allowed in.

Inside, Officer Clark was again being cross-examined. Clark explained that about 150 people had been at the dance that night, and that he had tried to get the names of additional witnesses—particularly those of three men who seemed especially focused on watching the defendants dance—but that they had refused to identify themselves. Throughout his testimony, the patrolman frequently referred to a small notebook he carried with him.

Atty. O'Connor became very interested in Clark's notebook and reached to take it. The officer pulled it away.

"Do you think I am a burglar?" asked O'Connor, eyebrows raised.

"I don't know whether you are or not," retorted the officer.

"If the Court would please instruct the officer to surrender his notebook?" suggested the lawyer to the judge.

"Officer Clark, you will allow Mr. O'Connor to see your notebook," ordered Judge Enright.

Clark grudgingly held out his notebook but his fingers seemed reluctant to release their grip. There was a brief tug-o-war over the rail before O'Connor gained the prize.

The lawyer began to read aloud from the notebook. Seven couples had been warned by the officer that evening. There was also mention of the fact that Clark had called Officer Swanwick's attention to certain dancers in order to back up his own observations. The booklet noted that Officer Swanwick had been at the hall all during the dance while Clark had come in late.

Then O'Connor took a new tack. "You said when I asked you if you thought I was a burglar that you didn't know whether I was or not?"

"Yes, I said that," replied the officer.

"Were you ever a burglar?" asked Atty. O'Connor.

"No."

"Didn't you break into Cahill's blacksmith shop, just across the street here, and were you not arraigned in police court for burglary and larceny?"

"How dare…" Clark sputtered. "Are you calling me a liar?"

"I object!" spoke up Supt. Welch. "Even if there was anything to these accusations, this line of questioning is highly irregular!"

"Mr. O'Connor," said Enright sternly, "You need to produce the papers in connection with the case if you want to continue this."

Ignoring Enright and speaking to the witness, O'Connor went on: "Did you not state that you had been tried for burglary when you filled out your civil service exam prior to becoming a police officer?"

"You Honor!" exclaimed Supt. Welch. "This is not material!"

"You'll stop this line of questioning, Mr. O'Connor," warned the judge.

"Wait a minute!" shouted O'Connor. "I want an answer!"

"Mr. O'Connor," growled Enright, "Enough. Please return to the case at hand."

"If this case is going to be about character," Atty. O'Connor roared indignantly, "We'll have the histories of all of us!"

"No, sir. We will not. And you are about to find yourself in contempt.

With that, things began to quiet down once more. "Mr. O'Connor, you may continue your cross-examination. But I'm ruling your current line of questioning out."

"Have you ever even seen a tango, Officer Clark?" began the attorney. "What makes you qualified to judge?"

"I've seen it done at the Vesper Boat house and other places around town."

Atty. O'Connor then questioned the witness about how the Lenten season put a damper on the local dance scene, and how Officer Clark might have felt pressured to bring charges against someone—anyone—before Lent started and opportunities for an arrest were fewer. Clark denied that being the case but O'Connor continued to push the idea that the defendants had simply been handy targets.

"Up to the last dance you didn't have Frank Hennessey and Angelina Marcotte under special observation, did you?"

"No sir."

"It is only of the last dance that you complained?"

"Yes."

"Did you see them before that time?"

"Yes, I saw them sitting in the hall."

"Were they indulging in unbecoming conduct?"

"No sir."

"Did you know Frank Hennessey?"

"No."

"You have no desire to have him or the young lady prosecuted, outside of doing your duty?"

"No sir."

"Did the crowd hiss you in the hall when you warned the first couple?"

"Yes sir."

"Was it a loud hiss?"

"Quite loud."

"You didn't feel very pleasant over it, did you?"

"I didn't mind it—I had been hissed before."

"Did you speak about being hissed? Didn't you complain or comment to anybody?"

"No sir."

"Didn't you say if the thing continued, there would be something doing?"

"No sir."

O'Connor's next move was to point out how conveniently precise the times offered in Officer Clark's testimony seemed to be. "How long had the defendants been dancing when you asked Officer Swanwick to watch them?"

"Ten or fifteen minutes."

"When did the dance begin?"

"At 11:35."

"How do you know?"

"I looked at my watch."

"Did Officer Swanwick look at his watch?"

"I think he did."

"Did you ask him to?"

"I did not."

"Have you some Marconi wireless system by which impulses are wafted through the air so that the two of you were in perfect synchronization?"

Clark ignored the sarcasm and answered flatly: "No sir."

"How long did the dance last?"

"Twenty-five minutes."

"You wanted Officer Swanwick as a witness?"

"I did."

"People come in pretty close contact, don't they?"

"At times."

"You have observed sweet, clean, wholesome boys and girls waltzing, and coming in close contact, haven't you?"

"Yes sir, but as a rule they do not come in very close contact."

"You couldn't put many sofa pillows between them, could you?"

"No."

"Not much more than a sheet of paper?"

"Oh yes, more than that," Clark protested.

"Yes, two or three sheets, I suppose," replied the attorney dismissively before pressing on: "Did you ever waltz yourself?"

"Yes."

"People come close together in that dance, do they not?"

"Yes." Clark scowled derisively. "Whenever they bump into somebody else!"

"How tall is Miss Marcotte?" O'Connor went on.

"About four foot ten or five feet."

"And how tall is Mr. Hennessey?"

"About five feet seven."

"Will you tell this court how they could have assumed the relative positions you described while dancing this morning? Wouldn't his body be up against her chin?"

At this point, reported the Boston Globe, Clark's "goat," which had been panicky for some time, abruptly flew the court.

"I think this is becoming a farce!" exploded Officer Clark. "You're trying to make a laughing stock of me!"

Judge Enright spoke soothingly: "Keep your head, officer. He has a right to cross-examination." Redirecting his attention to Marcotte and Hennessey where they sat on their side seat, the judge asked: "Would the defendants please stand up?"

The pair rose and Judge Enright looked them over carefully before waving for them to be seated once more. Atty. O'Connor returned to quizzing the witness for details.

"You've seen a number of people dance the dip?"

"I have."

"And it was the dip movement you objected to?"

"Yes, to a certain extent."

"Would the witness please describe what is meant by a 'dip'?"

"Why, they stand close together and duck their knees and bump…"

"You mean, I assume," suggested the attorney for the defense, "that it is nothing more or less than the interlocking of the knees of the participants."

"I suppose that that's a reasonable description."

Under further questioning, the officer stated that some people thought that all of the modern dances were crass and immoral but he felt that they were alright as long as they were danced properly. On the other hand, he believed that even the old-fashioned dances—the waltz, the schottische, and such—could be made inappropriate if danced in a vulgar fashion.

Atty. O'Connor then turned to the exact charges against his client.

"Will you describe a voluptuous emotion? Your chief speaks of it in his bill of particulars."

Clark gave a hint of a smile and opened his mouth to respond before thinking better of it. "I can't describe it," the officer hedged.

"Do you know that emotion is a matter of the mind?"

"I suppose it is."

"Then you would have to penetrate the minds of the dancers to observe voluptuous emotion?

"I suppose so. There are a number of things in the bill of particulars that were not my words. I didn't come up with 'lecherous,' 'lustful,' or 'voluptuous emotions.'"

"Who swore out the warrant?"

"The superintendent."

"And he was not at the hall when the dance was in order?"

"No."

"Were you present when the warrant was sworn out?"

"I was not."

"Who went with you when the arrests were made?"

"Inspector Walsh."

"You didn't fear any trouble from the young man?"

"No."

"What did you do when you entered the market where Hennessey was working?"

"I called him aside and served the warrant on him."

"What did you say to him?"

"I told him the warrant charged lewd, wanton, and lascivious actions."

"Did you know there has always been considerable doubt as to whether or not one act considered lewd, wanton and lascivious, constitutes a lewd, wanton and lascivious person?"

"I did not."

"Had you known that, you would not have made the arrests, would you?"

"Perhaps not."

The defense lawyer ran through more questions regarding the arrest and why Hennessey and Marcotte were singled out. He finished his cross-examination around 3:45 and Swanwick took the stand.

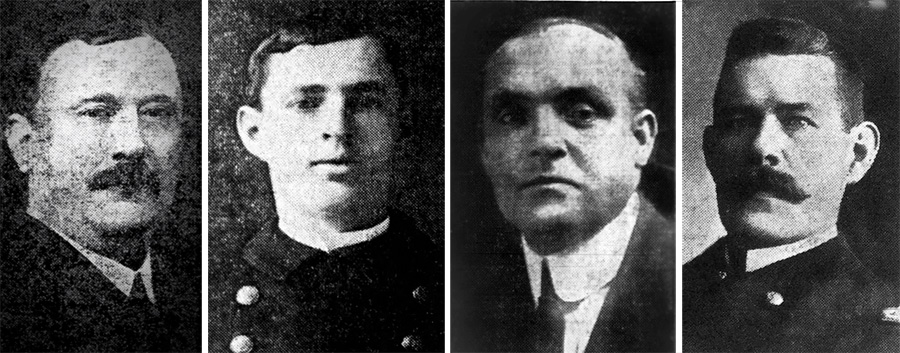

Left to right: Judge Enright, Officer Clark, Attorney O'Connor, & Superintendent Welch (adapted from newspaper images of the teens and '20s.)

Patrolman John W. Swanwick testified that he had been assigned to duty at Lincoln Hall on the night in question. He told the court of Officer Clark's appearance at the hall around 11 o'clock and that he, the witness, accompanied Clark into the hall. While there he saw the defendants go through wiggles and other improper motions.

"Why, they were twice as bad as what we showed you this morning!" exclaimed Swanwick.

The only question put to the witness by Atty. O'Connor was whether he, Officer Swanwick, had been temporarily suspended from the police force at one time for drunkenness. The witness admitted that he was once suspended for a term of seven days.

"But that was eight years ago and I haven't drunk on duty since. And it doesn't change the fact that what the defendants were doing at Lincoln Hall that night was disgraceful!"

"That's for the Court to decide," replied O'Connor firmly. "Your Honor, I'm done with this witness."

Supt. Welch spoke up: "The prosecution rests, your Honor."

Atty. O'Connor turned to the judge: "Your Honor, I move that the Court quash this matter for lack of evidence. My clients were charged under an old Puritanical statute that was never intended to include such cases, and the Court would have a long way to go to find the defendants were lewd, wanton, and lascivious. The prosecution has offered nothing to prove they are anything but decent, respectable people. This is an awful charge to bring against these two young folks. And I know, Your Honor, that when you take this matter under consideration, you will find it extremely difficult to sustain the charges."

"I will take your motion under advisement, Mr. O'Connor. Court is adjourned. We will reconvene tomorrow morning."

On Thursday morning, the extent of the ongoing interest in the tango-dip-schottische-waltz episode was made obvious by the reappearance of Wednesday's boisterous, surging crowds, crowds that jammed the courthouse doors almost to the point of obliging the officers to use their clubs. One journalist reported that it was comical to stand near the entrance and hear the excuses of the many folks who attempted to get past the men stationed there. About every other young man declared that he was a "member of the press," while another fifty or so would-be spectators claimed that they might be called as witnesses. And it was truly amazing the large number of "relatives" the two defendants had! But the blue coats were wise to it all and turned the majority away.

Inside, the court was again filled to capacity. Once the docket had been cleared of a few minor items, Assistant Clerk Trull called the dance case at 10:30. Mr. O'Connor requested that Miss Marcotte, Mr. Hennessey, John P. Curley and Dr. William P. Lawler be sworn in. After that had been done, Hennessey was called to the stand.

In response to questioning by his attorney, Frank Hennessey testified that he was born in Lowell and had always made the city his home. In his teens he had worked in Barrett's Grocery for five years and then, after various other jobs, took a position at Curley's Market on John Street as delivery clerk. His employer was John P. Curley, a meat and provisions dealer.

He went to the Buffaloes' dance in Lincoln Hall on Feb 19th at 8:45 and stayed to the end.

"After purchasing my ticket," Hennessey explained, "I went directly into the gallery and remained there until after intermission, at which time I checked my overcoat and went onto the dance floor. I danced with three different women, the last of whom was Miss Marcotte.

"Did Officer Clark warn you while you were on the dance floor?" asked Judge Enright.

"No, sir."

"What was the last dance?"

"A schottische, changing to a waltz."

"Will you tell the Court," said Mr. O'Connor, "If you danced the last dance in an improper manner?"

"I danced it the same as everybody else was doing it."

"What were the relative positions of your body and your partner's during the dance?" asked Mr. O'Connor.

"I had my arms about her waist and my hands rested on her shoulder blades."

"And where were her arms?'

"They were resting on my chest," replied the witness promptly.

"Then you were not in the attitude as described by Officer Clark and his fair partner yesterday?" asked the counsel for the defense.

"No, sir, never."

"What happened after the dance?"

"I went to the check room to get my coat and was met there by Officer Clark. He asked me for my name and address and I gave them to him. He said 'You're sure that's right?' and I told him it was. I then went out of the hall alone, as I entered it, and went directly to my home."

Satisfied, Atty. O'Connor turned to Supt. Welch: "Your witness, sir."

Welch began his cross-examination. "And you don't remember the movements of the body described by the police officers yesterday?

"No," replied the defendant.

"Do you want to deny that they took place?"

"Yes."

"Were you and your partner face to face?" asked the superintendent.

"Yes."

"And you did not have your arms around Miss Marcotte's waist?"

"No, sir. They were around her shoulders."

"And you now say that Officer Clark did not warn you?"

"Yes."

"What were you doing with Miss Marcotte?"

"I was dancing!" answered Hennessey, with a touch of exasperation.

"In the center of the hall?"

"No, around the sides."

Supt. Welch then went into Hennessey's arrest, Hennessey testifying that he had made no inquiry nor comment when told what the warrant was for. Welch concluded his questioning and the defense summoned their next witness to the stand.

John Curley, the young man's employer, testified that he had known the defendant all his life, and said that the boy's reputation for truth, veracity and character were of the very best. Dr. William T. Lawler added similar testimony. A third witness was called but failed to respond. To the great surprise of Supt. Welch and many others present, Lawyers O'Connor and Allard then announced that their case was closed. No testimony was submitted on behalf of Miss Marcotte.

Neither the superintendent nor counsel for the defendants submitted closing arguments.

Judge Enright returned his ruling immediately: "I am very sorry I cannot find sufficient cause to hold these two defendants. The police officers are absolutely justified in their efforts to stop these questionable and improper so-called dances but they are hampered because of the present laws. There is a law coming before the legislature soon which, if favorably acted on, will give the police power to stop these dances without the heavy burden of proof required in the present case.

"In making my finding in this case I base it principally on a 1901 decision handed down in the case of the Commonwealth vs. Dennis O'Brien, 179 Mass. 533. This was a complaint alleging that the defendant was a lewd, wanton and lascivious person in speech and behavior, the evidence being that on one night at two o'clock the police found the defendant under compromising circumstances in a room with two women.

"The aforementioned case specifically states that 'when the proof is confined to conduct on a single occasion, it does not sustain the complaint unless the conduct fairly warrants an inference that the defendants were persons of the kind described.' There was no evidence produced to show that these defendants were lewd, wanton and lascivious, except on this particular occasion, which was one occasion, and even though their actions then were improper, there is need of more evidence, as is described in O'Brien. I therefore can make but one finding, that of not guilty, and I order the discharge of the defendants."

The trial came to an end so abruptly that it rather staggered the large gathering of interested spectators as well as the officers of the court. Superintendent Welch, the big prosecuting officer, stood somewhat aghast when the announcement was made, while little Angelina Marcotte, wreathed in smiles, hurriedly made her way to the outer room to be met there by some of her friends. Frank Hennessey, his face flushed at the very favorable outcome, chuckled and laughed with his counsel, Atty. O'Connor.

Outside of the building, where hundreds had gathered, the news of the court's decision was received with shouts, and when the principals appeared in the doorway, they were greeted with a mingling of cheers and congratulations. The Lowell Sun six o'clock edition ran a full width banner headline: "TANGOISTS NOT GUILTY."

Although special Officer Clark bemoaned his defeat, he was broadminded enough to admit that "right is right" and if the court couldn't find sufficient evidence to convict, the finding was just as it should be. He did say, however, that the work of eliminating questionable and improper actions in dance halls would go on, and that the disposition of the present case didn't mean that demonstrations of the "teasing tango" and other terpsichorean novelties could continue unchallenged. He was not alone in his determination to keep up the fight; Superintendent Welch and Mayor Dennis J. Murphy made it clear in the following days that they were right there beside him.

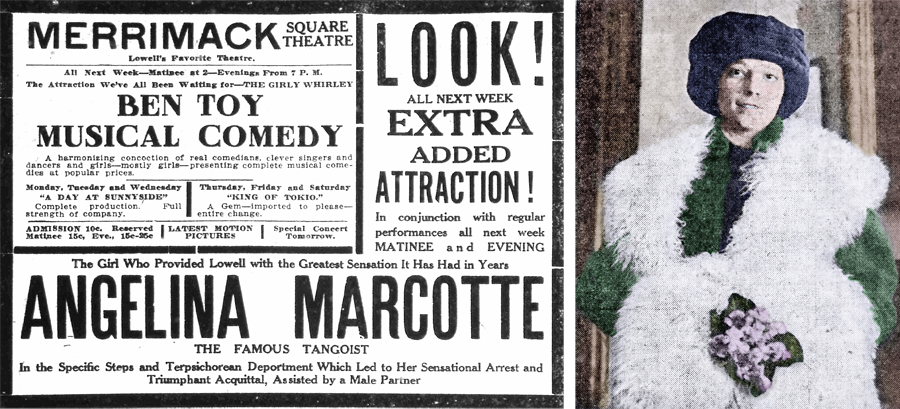

Although Frank Hennessey was happy to quickly fade from the headlines, Angelina Marcotte was less eager to go back to laboring in obscurity at menial tasks; a savvy promoter offered her a way out. A large advertisement for her addition to the bill at a local Vaudeville theater appeared in the Lowell Courier-Citizen morning edition on March 7th, just two days after the verdict, along with a long article describing all the acts being offered. The article ended with details about Marcotte's impending performance:

"Angelina Marcotte, the engaging young miss who, for the past week, has been the cause of furnishing Lowell with the greatest sensation it has had in years, will be an added attraction the coming week at the Merrimack Square Theatre. She will appear in conjunction with the regular bill and will at each and all performances give a specific demonstration of the tango, which caused her arrest and subsequent acquittal.

"A record-breaking crowd will no doubt be on hand the coming Monday afternoon to view the exhibition and that they won't be disappointed in seeing real 'class' in terpsichorean deportment is an assured fact. She will be assisted by a dancing partner direct from New York.

"Miss Marcotte will make her appearance in a beautiful dress designed especially for this purpose, while her partner will appear in evening dress. The musical accompaniment is being arranged with regard to that raggy syncopation which is absolutely necessary in doing the proper steps at the proper moment. On the coming Tuesday and Friday afternoons special performances will be given, and after them free lessons to all who desire to learn."

Vaudeville advertisement and photograph of Angelina Marcotte, both from Lowell Courier-Citizen, March 1914 (photo colorized by author)

Given that this new star claimed she didn't even know how to tango two weeks earlier, one has to wonder just what Angelina would be dancing. The draw here was obviously salacious rather than anything to do with dance skill. Which was exactly how Mayor Murphy saw it. From the Lowell Sun's evening edition that same day.

"MAYOR MURPHY AGAINST TANGO

"Engagement of Miss Marcotte at Merrimack Square Theatre Threatens to Take Away Sunday Entertainment Privilege

"Will Angelina Marcotte tango at the Merrimack Square theatre? Well, perhaps so and then again, perhaps not.

"A three-column advertisement tells us that Angelina will trip the light fantastic at that cozy playhouse, but something happened since the 'ad' was written and inserted. Angelina is booked as 'the famous tangoist' and it is stated that she will be seen in 'the specific steps and terpsichorean deportment which led to her sensational arrest and triumphant acquittal, assisted by a male partner.'

"Mayor Murphy read the notice in the paper and after giving the matter due consideration, dictated the following letter which, in its personal reflection on Manager Carroll will be considered needlessly severe by those who know that gentleman, regardless of their views in reference to the tango.

'March 7, 1914

To the Management of the Merrimack Square Theatre, Lowell, Mass.

Sirs:

I notice in your advertisement in the Lowell Courier-Citizen today that you advertise Angelina Marcotte to appear at your theatre for the week beginning March 9.

If you believe that this is the character of entertainment and sensationalism that the people of Lowell are waiting for, it satisfies me that you are not a proper person to conduct Sunday entertainments in your house, and while I have no authority to prevent you from employing Miss Marcotte in your theatre, I can assure you that if she appears I will not grant any license to your house to conduct performances on Sundays.

Very respectfully

Dennis J. Murphy

Mayor of Lowell'

"Asked if he had anything to say relative to Angelina's tangoing or the mayor's letter, the manager of the Merrimack Square theatre, F. J. Carroll said: 'There isn't anything in particular that I care to say just now. You may hear from me later.'"

But by the end of the weekend Mr. Carroll capitulated. The following article appeared in Monday's Lowell Courier-Citizen:

"MISS MARCOTTE IS WITHDRAWN

"Mayor Protests Against Her Appearance at a Local Theatre

"Angelina Marcotte, who was advertised to appear at a local theatre this week, in 'the specific steps and terpsichorean deportment which led to her sensational arrest and triumphant acquittal,' has been withdrawn from the bill, at the specific request of Mayor Dennis J. Murphy.

"'I have nothing against the Merrimack Square Theatre, or its management, or any other theatre in the city or its management,' said the mayor, 'but I did, in requesting Mr. Carroll to cancel the engagement with the woman, locally at least, what I believe to be wholly within my province, and for the best interest of Lowell. I do not consider that the woman in the case should be paraded on any public stage. Hence I sent a letter by special messenger to Mr. Carroll, informing him that if he persisted in keeping this woman on the bill I would revoke his license for Sunday entertainments. We have had our fill, and more, of this tango business, and it does Lowell no good, either at home or abroad. Many, many calls from citizens who are heartily disgusted with the whole thing have come to my attention since the publication of the advertisement, and I know they represent the very best element in this city. They represent all sorts and conditions of men so far as worldly goods go, but they want something besides the tango forced upon their attention all of the time. I agree with them, but my mind was made up before they had called me.

"'Mr. Carroll came up to City Hall to see me shortly after he had received my letter to him. He asked me about the letter and I told him that I did not want the woman to appear on the stage of his theatre. He said that if that was my request he would cancel her local engagement at once. This I accepted as final, and I am sure he will live up to his word.'

"Manager James Carroll of the Merrimack Square Theatre was non-committal on the matter of the mayor's request, although he did state that he had Angelina Marcotte booked for 15 weeks, presumably in other theatres on the circuit."

Banning Marcotte from the local stage was not the only step Mayor Murphy took to make it clear that the verdict was not going to stop him from enforcing proper behavior in Lowell's dance halls. The Lowell Sun reported a second letter from the mayor that also went out on the seventh.

"MUST NOT TAKE TICKETS

"Police officers have been in the habit of taking tickets at dances but they mustn't do it any more, for the mayor himself hath said it. He says they must give their whole and undivided attention to police work, and he sent the following letter of instructions to Supt. Welch of the police department this forenoon:

'Lowell, Mass., March 7, 1914

Redmond Welch, Supt. of Police:

Dear Sir—I hereby notify you that on and after this date all police officers assigned by your department to dance halls shall devote their whole time and attention to police work and they will refrain from acting as ticket takers. It is not the duty of a police officer to act as a ticket taker; he should devote his whole time and energy to the supervision of the dancer with the sole idea in mind of maintaining order and decency,

Respectfully yours,

Dennis J. Murphy, Mayor'"

Nor was Superintendent Redmond Welch shy about expressing his own determination to keep those evil modern dances in check.

"We must, and, what is further more, we will, stop these vulgar dances," vowed the big chief in the Lowell Courier-Citizen. "The average person wants it stopped and it's certainly going to be checked."

"I am satisfied that at least 99 per cent of the people of Lowell want these improper dances stopped and I am going to ask the license commission to help me by revoking the licenses of those who own public halls if they fail to assist the police in the work. I intend to ask, yes, demand, the owners of halls see to it that all objectionable persons be ejected from their places once they become imbued with the idea that they can dance away from the path of righteousness.

"In view of the shortcomings of the present laws to cope with the conditions, I believe that every one who is interested in seeing decency prevail will assist in the work. I would ask these persons, when in attendance at one of these functions, to act as a committee of one and help in the work. If they will, then conditions will be corrected in short order.

"There will be no more warnings by officers. The latter will go around to the halls as usual, and if they can bring a person or persons into court on evidence that will show two or more occasions when they indulged in this questionable pastime, there will be more court proceedings.

"We now know, as a result of the recent finding, which I believe was perfectly right on the evidence and the interpretation of the law, that a person to be convicted under such a charge must be guilty of more than one specific offense. The shortcomings of the present laws require it. The proposed legislation, recently introduced by Representative Lewis Sullivan of Dorchester, will not remedy the evil, I think. As I understand it the so-called tango and all other modern dances can be indulged in with as much propriety as any of the old-fashioned dances. I believe, with Prof. O'Brien, who appeared against the proposed bill, that it all comes down to a question of the individual and it is dealing with the individual and not with the dances that will result in correcting the wrongs.

"Oh, yes, we'll stop it," said the superintendent in conclusion.

It's rather interesting reading Welch's statement about "seeing decency prevail" given how his career eventually came to an end. Apparently he found dancing much more threatening to society than gambling or intoxicating liquors. His downfall came when Prohibition passed and he had no stomach for enforcing it, eventually getting himself in trouble not only with the city government but with the Feds as well. Within hours of George B. Brown being installed as Lowell's mayor in January of 1922, Redmond Welch was removed from his position as Superintendent and the police were instructed to clamp down on the serving of alcohol.

But Welch did not go quietly. After a protracted legal battle he was reinstated in May, removed again by the mayor two days later, and then retired at half pay. He passed away two years later after a long illness.

The superintendent's main adversary during the tango case had an even shorter, bleaker future following the acquittal. Atty. John Joseph O'Connor married in 1916 but widowed his new bride just eight months later when, having fallen into a deep depression brought on by health issues, he shot himself in the head at his office on Central Street. He was in his mid-forties at the time. A life-long resident of Lowell, a respected lawyer, and a local politician as well, the February 1917 funeral for O'Connor was quite the affair and involved a half-dozen clergy, a high mass at St. Patrick's church, and a well-attended burial at the O'Connor family plot in St. Patrick's cemetery. The Church seems to have thought highly enough of Mr. O'Connor to have forgiven him his suicide and allowed his burial in hallowed ground.

The second defense lawyer in the case fared much better. Atty. George H. Allard, Marcotte's lawyer of record, married in 1921, worked out of an office on Merrimack Street until 1948, and then worked from home for another year before retiring. He died in 1951 at the age of 62 and was buried at St. Patrick's cemetery with military honors.

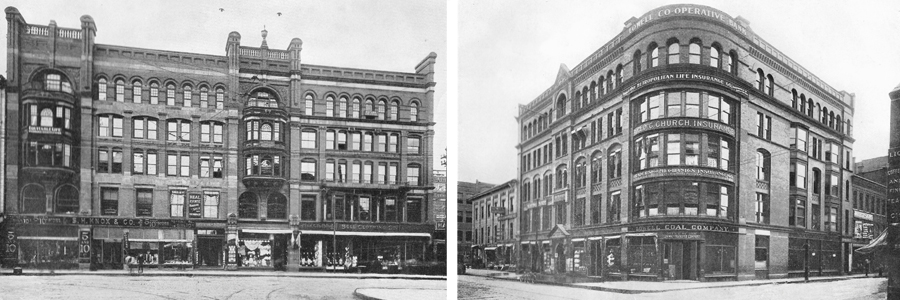

At the time of the trial Allard had his office in the Hildreth Building (left) and O'Connor's was in the Central Block (right). Shown c.1904

The tango trial's presiding judge, Thomas J. Enright, had a distinguished career serving on the bench in Lowell and died in 1927 at the age of 67 after a long illness.

As for the dancing police officers, Officer John H. Clark remained in his special role as part of Lowell's liquor squad until July of 1916 when he returned to regular patrol duty. The newspapers continued to occasionally tease him for months after the tango trial—one report about the arrest of a drunk calls the man's inebriated swaying a "tango" and describes his near-fall as a "dip" "that would make Officer Clark envious"—but eventually the world moved on and the escapade was forgotten. In May of 1930 Clark was promoted to the rank of sergeant and in 1932 was put in charge of the vice squad. He fell ill just a few months later and died in February of 1933 after 27 years on the Lowell police force, leaving behind a wife and three daughters. He, too, was laid to rest at St. Patrick's cemetery.

Officer Swanwick stayed a patrolman for the rest of his long career, retiring in 1946 after 40 years on the force. He passed away in 1949 at the age of 72, leaving behind his wife of 51 years, two daughters, a son, three grandchildren and a great grandson. Unlike most of the other players in this story, he is buried in Edson Cemetery rather than St. Patrick's.

Frank Hennessey, as it turns out, was not exactly Frank Hennessey. Although he used Frank for most of his life, his given name was Cornelius Frank Hennessey. His marriage records list him as Frank Joseph Hennessey, Joseph likely being his confirmation name. In any case, following the trial Frank quietly went back to clerking at Curly's Market. In 1916 he married Miss Amy Mahue of Concord, New Hampshire, and brought her back to Lowell to live. During WWI he labored for the United States Cartridge Company, almost certainly in the Market Street mill complex that was converted to munitions manufacture during the war, which means he would have been working right next door to the trial site. Following the war, Hennessey worked as a shipping clerk until he died at the age of 36 in 1926 while being treated at St. John's Hospital.

And Miss Angelina Marcotte? That's one mystery this author has been unable to solve. The newspapers reported that she was born in Canada of French stock around 1894 and that she had moved from Manchester, New Hampshire, to Lowell a year before the trial. That makes her something of a transient as far as Lowell records are concerned and her name doesn't appear in any directories or local censuses. She was supposed to have begun a fifteen week tour on the Vaudeville circuit yet this author hasn't found her name in any newspaper advertisements. She certainly didn't go back to working at the boarding house; the owner of that establishment relocated to Lynn before the year was out. Where did she go? What did she do? Did she marry, change her name, return to New Hampshire or Canada, or pass away? Alas, we may never know. But for a few days in the winter of 1914, Miss Angelina Marcotte and her dance partner, Mr. Frank Hennessey, were absolutely the talk of the town.

The Donohoe Building, once the home of Lincoln Hall, as it looks today (photo by R. Evans 2022)

Overview of source material:

This story relies heavily for both narrative and dialogue on newspaper reports from the Lowell Sun, the Lowell Courier-Citizen, the Boston Globe, and the Boston Post from February 23rd through March 7th of 1914. These newspapers were accessed through multiple online subscriptions, and through the microfilm collections of Lowell's Pollard Memorial Library and the Boston Public Library.

Further resources include, but are not limited to, the Lowell Cultural Resources Inventory Report (1980); local cemetery records; WWI draft records; Massachusetts birth and death records; Lowell Massachusetts city directories 1913–1950; United States Federal Censuses 1880–1930; Round Dancing, an 1890 dance manual by M. B. Gilbert; dozens of U.S. newspaper articles and obituaries ranging from 1880 to 1950; The History of Lowell and Its People, Vol. 1–3, by Frederick Coburn (1920); Views of Lowell and Vicinity (1905); marriage records from New Hampshire and Massachusetts; The Prison Officers Hand Book issued by the Massachusetts Board of Prison Commissioners in 1905; Twirling Jennies: A History of Social Dance (and other mischief) in the City of Spindles 1820–1920 by yours truly; ancestry.com; familysearch.org; newspaperarchive.com; newspapers.com; archive.org; books.google.com; extremeweatherwatch.com; and the author's own decades of dance experience, research, and performance, including but not limited to American and English contras and quadrilles, and historic and modern ballroom.

The author would like to express her gratitude to the reference librarians, cemetery records folks, and various friends, acquaintances, and family members who've aided and encouraged her in putting together this narrative.

The Old Market House, formerly the Lowell Police Station & Court (photo by R. Evans 2015)

|

|

|