|

|

|

| The young city of Lowell didn't skimp on celebrating Independence Day. This was especially true in the run-up to the Civil War as residents proclaimed their patriotism and prayed that the union would survive—especially given the thousands of local jobs that depended on a steady supply of southern cotton. July fourth of 1858 fell on a Sunday, bumping the official celebration to Monday, and this three-day weekend was filled with activity. On Saturday there was the Pentland Circus's Grand Parade through town to whet the public's appetite for their two shows on Saturday and three on Monday (admission $ .25). Sunday there were church services, both the usual morning ones and a combined evening one at Huntington Hall. Monday included a sunrise salute fired from both commons, bell ringings, and a large parade made up primarily of the city's schoolchildren who were, for this event, labeled the "Band of Hope." There was a Balloon Ascension on the South Common. Fireworks companies hawked their wares in the local papers—Rockets, Torpedoes, Pinwheels, Serpents, Roman Candles, Grasshoppers, Palm Trees, Pops, Blue Lights, Pigeons, Lanterns, and more—and the Board of Alderman, while not exactly suspending the relevant rules during Monday's celebration, made it a point to issue a special notice that Lowell police must diligently enforce regulations against discharging firearms and fireworks in the city before 3:00 pm and after midnight.

Somewhere in the midst of all this, on the Fourth itself, Reverend E. B. Foster presided over the marriages of both Melbourne Francis Hutchins and Melbourne's sister, Mary Jane, at the Congregational Church on John Street. It must have been amusing—and confusing—to see Mary J. Hutchins become Mary J. Kimball at the same time that Mary J. Grover became Mary J. Hutchins. Following the wedding, Mary and Allen Kimball headed home to his farm in Littleton where Mary would play stepmother to the widower's young daughter. Whether Melbourne immediately took up the farming life with his bride or instead kept house with her for a time in his rooms on Central Street is unclear, but it seems likely that the newlyweds soon set out for Westford where the Hutchins family had been farming for generations.

Melbourne Hutchins was born Francis Melbourne Hutchins on June 15th of 1837 but throughout his life he went by Melbourne Francis, even on the dozens of legal documents to which he was a party over the years. His father, Stephen Hutchins, owned a hundred acre farm in Westford with over a dozen head of cattle, a similar number of sheep, two teams of oxen, a half dozen hogs, and all the hardware, wagons, tack, plows, and equipment that went into keeping the farm running. The farm had come to Stephen Hutchins through his own father, and in exchange for ownership, Stephen was required to provide support for Melbourne's aging grandparents and another woman of similar age, Miss Anna Pierce, for the rest of their days. But Stephen Hutchins did not survive to see this duty through. When Melbourne was five years old, his father was killed by an iron bar while moving a large stone in New England's notoriously rocky soil.

Melbourne's mother, Catharine, chose not to administer the estate herself; she already had her hands full with the farm and four children between the ages of five weeks and ten years. Instead, she requested her late husband's brother, Eliakim Hutchins Jr., be appointed administrator. And to handle the legal status of her children regarding their inheritance, she petitioned the court to appoint her brother, Leonard Butterfield Jr., as guardian. Because Melbourne's father had died without a will, settling his sizable estate would drag on for the next decade an a half, drawing in various family members and friends for support, and involving the probate courts of Cambridge, Concord, Lowell, and Groton. During this time, the estate paid out money for the support of the three "old folks"—now living with Melbourne's aunt and her family—and took in money from Melbourne's new stepfather, Robert Taylor, who had taken over running the farm.

Gradually the Hutchins children grew up and were drawn to the bustling city of Lowell next door. The eldest, Stephen Eliakim Hutchins Jr., was the first of the family to take up residence in the rooms over French's Confectionery. But when he married in 1855 he returned to the farming life in Westford. His sister, Mary Jane, was next to move into that address, followed shortly by Melbourne, who took work as a driver. But like their elder brother, they both seem to have left the city when they married.

By the time of Melbourne's marriage to Mary J. Grover, daughter of a Lowell machinist and die cutter, Melbourne's mother, stepfather, and two young half-siblings were living in Westford on a section of the family farm that had been carved out under the widow's right of dower. The exact status of the rest of the property is unclear, but it seems the sons were able to readily return to farming in Westford when they so chose. The year of Melbourne's marriage was also the year that his uncle, Leonard Butterfield, passed away and Melbourne stepped into the role of legal guardian to his two youngest brothers, then ages fifteen and seventeen. But much as he tried to play the role of loving husband and responsible brother, things went awry. |

|

|

| One of a variety of advertisements in the Lowell Courier leading up to July 4, 1858. |

|

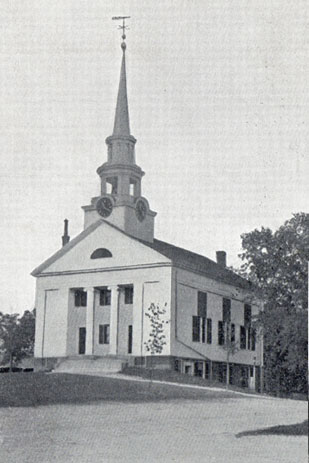

| The church where the Hutchins' weddings took place in 1858, as shown in that year's directory. |

|

| The restored kitchen hearth at the Hutchins family farm (2017). More pictures of the farm as it looks today can be seen at zillow.com. |

|

| An advertisement for Melbourne's (former) father-in-law's business from the 1868 directory. |

|

|

|

In February of 1859, after only seven months of marriage, Melbourne's wife abruptly packed up and went home to her family. Mary's actions seem to have caught her husband totally off-guard and one wonders just what happened. Was Melbourne less than the "faithful and affectionate husband" he claimed to be, or was the isolation of a New England winter on a country farm simply too much for a city girl already struggling with her new role as wife? Either way, the next year or two found Melbourne living alone and farming in Westford. Eventually he moved to Tewksbury where he again took work as a driver, also known as a "teamster" after the team of draft animals the driver was required to manage. |

|

|

|

| Although Hutchins was eligible for duty in the Union Army—his draft rating was "Class I" in 1863—no evidence has been forthcoming that he was actually called to service during the Civil War. His two younger brothers, however, did serve and both of them perished. Corporal Edward Everett Hutchins was killed in May of '64 at the Battle of Resaca, Georgia, and Private Warren Hutchins fell to consumption at Duvall's Bluff, Arkansas, that November. Now, instead of guardian, Melbourne was forced to step in as estate administrator for Warren. That was not his only dealing with the court system that year; that spring Melbourne had petitioned for—and been granted—a divorce from Mary Grover on grounds of desertion after five years of living apart. For Mary's part, she ignored the court summons to appear and let the charges go uncontested. Mary Grover would continue to reside with her parents, working some of the time as a seamstress, for another eighteen years before finally remarrying.

Not long after his divorce, Melbourne moved back to the lodgings over French's Confectionery and renewed his business relationship with Levi Nichols and Amos French—if it had ever lapsed in the first place. It's quite possible that Melbourne's job as a teamster while living in Tewksbury included hauling goods in and around Lowell for the Central Street establishment. Early in 1865, all three men cosigned the two-thousand-dollar bond that Melbourne was required to post as administrator of Warren Hutchins's estate, hardly a commitment to be taken lightly. Lowell's 1864 directory lists Levi Nichols as proprietor of A. B. French & Company, and Amos French and family as simply boarders on the property. Another source claims that Levi Nichols and Melbourne Hutchins were both co-owners of the restaurant as early as 1863. Whatever the exact situation, it's quite clear that Melbourne Hutchins's temporary departure from Lowell had not severed the connections between the three men. And the bonds were not just professional.

On April 13th of 1864, Amos French's niece (Thomas French's daughter) married Charles Henry Pierce of Chelmsford. A year later, on April 9th of 1865, Melbourne Hutchins married Pierce's sister, Julia. Melbourne and Julia were wed at Chelmsford's First Parish Church, a Unitarian/Universalist/Congregationalist hybrid at the time, and the newlyweds settled into their living quarters in Lowell above the Central Street confectionery. This marriage fared much better that Melbourne's first, and there were no more unwelcome surprises for him regarding runaway brides. [The Pierce name turns up repeatedly in this story. Thomas French's wife was also a Pierce, as was the elderly woman, Anna Pierce, that Melbourne's father had agreed to support as part of his obtaining the Hutchins farm. I have been unable to definitively link the different Pierces.] |

|

|

| Above left: The Hutchins farm as it appeared in 1900 (from The New Old Houses of Westford by Ellen Harde & Marilyn Day, courtesy of Westford Historical Society) Directly above: Illustration of a teamster picking up goods to deliver. |

| |

|

| The First Parish of Chelmsford, c. 1905, from a vintage postcard. |

| Amos French soon went his own way and left the business in Nichols and Hutchins's capable hands. Between late 1866 and mid 1873, Melbourne Hutchins was able to pay off various mortgages and gradually buy up several shares of the family farm from his siblings and stepfather. In November of 1868 Julia Hutchins gave birth to a son, Charles Warren Hutchins.

With sizable nest eggs set aside and French's original land lease with Jonathan Tyler expiring, plus growing families for both men, Nichols and Hutchins decided to sell off their business in 1872 to Benjamin Goddard, a former merchant and grocer, and to his son, also Benjamin Goddard, a painter. Nichols and his family settled into a house at 101 Westford Street while Hutchins and family headed back to the farm in Westford. |

|

|

|

|